Immune cells play surprising role in heart: Study

New

research in mice suggests that certain immune cells may help guide

fetal development of the heart and play a role in how the adult heart

beats, according to a news release posted this week on the website of

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The researchers analysed genetically modified mice that lacked B cells, and found that their hearts were smaller and contracted differently than the hearts of normal mice, the Xinhua news agency reported.

The researchers analysed genetically modified mice that lacked B cells, and found that their hearts were smaller and contracted differently than the hearts of normal mice, the Xinhua news agency reported.

Advertising

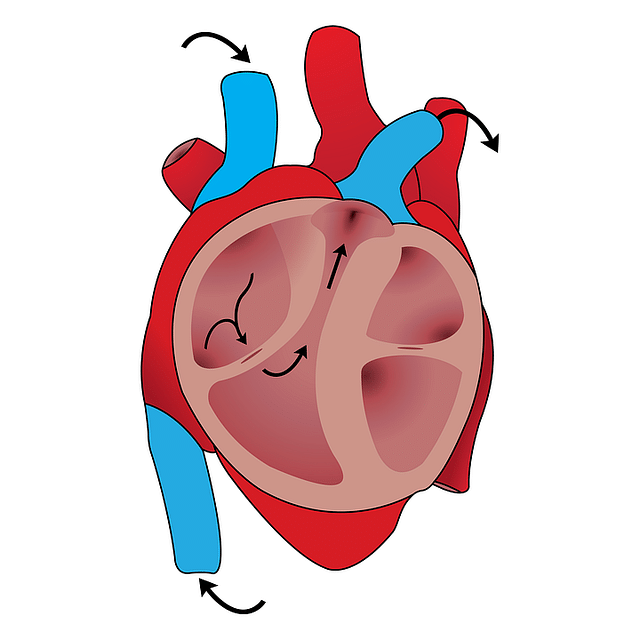

The

hearts of mice missing B cells relaxed faster and pushed more blood out

of the left ventricle with each beat. The researchers also found that

in such mice, the number of T cells, a different type of immune cell,

doubled in the heart.

"We

are working on more studies to learn if the missing B cells have a

direct effect on the structure and rhythm of the heart, or if we are

seeing some indirect effect during development or through the change in T

cells," said the study's first author Luigi Adamo, an instructor in

medicine. "But that removing B cells had any effect on the heart is

completely unexpected."

B cells are a type of white blood cell well-known for their role as sentinels that circulate in the bloodstream and manufacture antibodies to fight off infection.

B cells are a type of white blood cell well-known for their role as sentinels that circulate in the bloodstream and manufacture antibodies to fight off infection.

Focusing

on B cells that appear to hang out in the heart, the researchers were

surprised to find that these cells neither freely circulate through the

body's blood vessels nor reside permanently in the heart muscle. Rather,

these particular B cells were found lingering in the small blood

vessels that feed oxygen and nutrients to the heart muscle.

"Because they were in the blood vessels, it was conceivable that they were only a random sample of circulating B cells," Adamo said. "But when we compared their active genes to those of freely circulating B cells, we found that there was something special about them: This is a type of circulating B cell that arrives in the heart vasculature and becomes sticky."

These sticky B cells still circulate through the heart, the blood and spleen, but they slow down considerably, taking their time as they transit through the heart vasculature.

The findings have opened a door to possible immunotherapies to protect the heart and other organs that might also see this B cell behavior, according to the researchers.

The findings have been published in the journal JCI Insight. - Collected from "Prothom Alo"

"Because they were in the blood vessels, it was conceivable that they were only a random sample of circulating B cells," Adamo said. "But when we compared their active genes to those of freely circulating B cells, we found that there was something special about them: This is a type of circulating B cell that arrives in the heart vasculature and becomes sticky."

These sticky B cells still circulate through the heart, the blood and spleen, but they slow down considerably, taking their time as they transit through the heart vasculature.

The findings have opened a door to possible immunotherapies to protect the heart and other organs that might also see this B cell behavior, according to the researchers.

The findings have been published in the journal JCI Insight. - Collected from "Prothom Alo"

No comments

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.